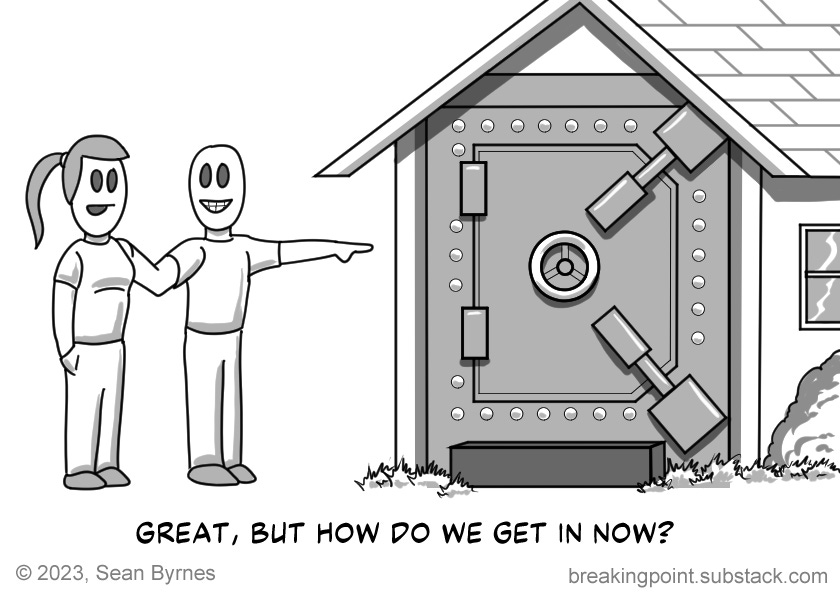

Beware One Way Doors

Don’t waste time over-analyzing decisions you can easily change. Focus on the decisions that you can’t change later.

Jeff Bezos, who needs no introduction, has a great framework for thinking about how much time to spend on making a decision. Specifically, he has two categories of decisions:

Type 1. These are one-way doors, decisions that cannot be undone. These are serious decisions that require a lot of time to make them well, since you’re stuck with the decision later. Examples include quitting your job, raising capital and selling your company.

Type 2. These are two-way doors where it’s easy to change the decision later. Most decisions fall into Type 2, since most decisions can be undone. For example, if you launch a new product feature and it doesn’t work you can just revert the change.

You don’t want to spend the heavyweight time and process on Type 2 decisions that you would on Type 1 decisions! And yet, as companies get bigger they start to do exactly that. It’s one reason that companies move more slowly as they grow.

Read Jeff’s excellent description of this framework in his 1997 Amazon shareholder letter.

Like any framework, this is both beautiful in its simplicity and extremely difficult to apply to your own decision making process! Whether or not a decision can be undone is difficult to ascertain in the fog of war, and the answer also changes over time.

For example, is launching a product a Type 1 or Type 2 decision? It would seem to be an easy question, since you can easily end a product if the launch isn’t successful. However, what if your company only has 9 months of runway? Do you have the time to undo the decision and try it again? Probably not, you only have one shot which makes it a Type 1 decision.

It’s also difficult to think objectively about decisions due to influences like the sunk cost fallacy. If you’ve spent 12 months building a new user interface for your product, is the decision to release it Type 1 or Type 2? Objectively it’s a Type 2 decision, since you can easily choose not to release it. However, after investing so much time and effort it might seem like you have no choice but to follow through and hence make it a Type 1 decision. After all that time and effort it can seem impossible to tell everyone you are just throwing away their hard work. Again, in the fog of war that is our daily business operations it’s hard to be a perfectly objective operator.

To help you, here are some shorthand rules I use to tell the difference between Type 1 and Type 2 decisions.

It might be a Type 1 decision if…

You are signing a contract that lasts more than 12 months. A year is a long time for most companies, and not being able to change your mind for that long may lock you in. (Speaking of which, that is one reason most enterprise software contracts are for 12 months).

It involves firing people. Layoffs, firing and other ways of reducing your team size are almost impossible to undo for obvious reasons.

It will occupy most of your focus for the next six months. Focus is a rare resource and you can only have one number on priority, so if you’re choosing something you’re ignoring everything else. You cannot go back and reclaim that time.

You’ll notice that most of my criteria for Type 1 decisions is whether you lost something valuable. Time, people or money are all extremely valuable and difficult to replace. How much time, people or money is important depends on the size of your company.

It might be a Type 2 decision if…

The effort involved is trivial. Doing something a second time isn’t so bad if it’s easy!

No one will be able to tell. If no one will notice a change, it can’t be that important.

You are running a test. Hopefully your tests aren’t permanent.

It’s not a Type 1 decision.

The easiest way to spot a Type 2 decision should be that it’s not a Type 1 decision, but maybe not? I once worked with a company that used the WORST video conferencing software imaginable, which made everyone at that company miserable. They should have been able to switch to a better vendor, but the executive leadership signed a 7 year long contract with this bad vendor. What should have been a Type 2 decision became a Type 1 decision through bad leadership.

Be careful out there!

Speaking of Mistakes…

One of the most useful applications of this framework, beyond saving time, is to help your team make mistakes. Everyone needs to make mistakes to learn, it’s one of the best ways to grow as a person and level up in your job. As a leader, it can be really hard to let your team make mistakes and especially so if you know the correct decision they should have made. And yet, if you make all their decisions for them, and don’t let them make mistakes, your team will never grow.

Applying this framework, we want to make sure our teams only make mistakes on Type 2 decisions. In those cases, we can undo the mistake later, after they have learned from it. If they make a mistake in a Type 1 decision we’re stuck with it forever, so that is the time to step in and override their decision to avoid the mistake. I’ve found that this approach greatly reduces your anxiety about allowing mistakes as a leader, and empowers your team to grow more quickly. Just be sure you’re sure that the mistake they are going to make is a Type 2 decision!

What if you’re wrong?

Of course, as I said before, these frameworks are hard to use in your everyday work. What happens if you incorrectly classify a Type 2 decision as Type 1? It happens all the time, especially with founders who haven’t raised Venture Capital before and don’t realize that fundraising is a Type 1 decision. In business, like in improv, you have to deal with what is presented to you instead of wishing the world was different. When we treat a decision incorrectly, we learn and move forward.

Next time you’re making a decision, first decide if it’s Type 1 or Type 2. Then, make sure your team is doing the same, so that your company never starts to conflate the two. Avoiding that trap, and not spending too much time on Type 2 decisions, will become a competitive advantage for you as you scale.

For more on decision frameworks, see these posts:

Making choices means choosing the Types of Risk you prefer.

Before deciding, ask yourself What’s the Worst That Could Happen?